Operational Excellence

A Communication Story: Tunnel Freezer vs Ammonia Pressure

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While working with a seafood company, one of their individually quick frozen (IQF) seafood products had become quite popular. This product required a belt type tunnel freezer to freeze the portions. Due to the popularity, the tunnel was running double shift, and still not able to keep up with the demand. As an industrial engineer, I was asked to look at the productivity numbers, and determine if they needed an additional freezer.

I set about tracking the numbers, and studied the operators, and realized there was very little additional belt time we could get from the existing freezer. There was no waste on the changeover between different species of fish, and the conveyor was seldom empty through the course of both shifts. Some of you that are familiar with the food industry will notice that I missed an obvious side of this problem. I did try speeding up the conveyors, but then the tunnel did not do an adequate job of freezing the seafood.

We set about doing some planning and came up with a preliminary cost estimate for a new tunnel freezer, and where it would be installed. We had all the appropriate departments assemble in the plant manager's office for a meeting, to finalize the presentation data the plant manager would make to the company board members. Our best estimate was that the freezer, combined with its cost and installation in the plant, would be a million-dollar project. The cost was affordable, as the value of this new IQF product going out was multiple millions of dollars per year. This product was so good that it justified a high premium over fresh fish fillets.

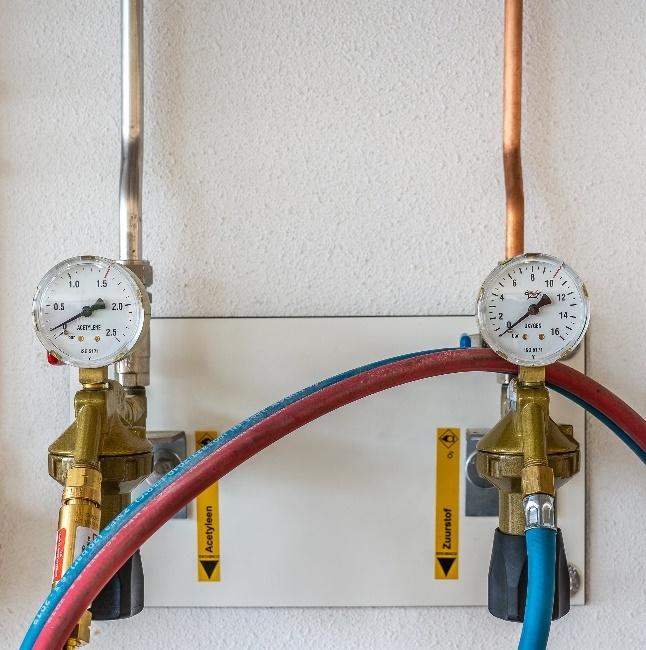

We are sitting around the office, discussing the finer points of the million-dollar proposal, when my boss, the Engineering Manager, goes quiet, shakes his head, and then makes a comment to me. “Walter, I bought that machine 20 years ago, and when I bought it the rating was 2000 pounds per hour. Why is it only doing 1100?” I pointed out that the machine was reasonably old, and we could only expect a smaller volume from the machine now. My manager thought about this for another minute, and then turned to the maintenance manager. He asked the maintenance manager what pressure he was running the ammonia compressors at for the refrigeration cycle.

The manager responded that he was running the compressors at a number which I remember as being about 150 psi. The engineering manager responded that those compressors could run as high as 180 psi under normal loads. The maintenance manager responded that yes, the compressors could run at a higher psi quite safely. However, he kept the pressure down so as not to spike our electricity load to the local utility. A spike would result in a $10,000 fine, for every time it occurred during the month.

The room went a little quiet at this point, though the silence seemed to escape the attention of the maintenance manager. The plant manager turned to the maintenance manager and asked if any of the electrical load could be transferred from the day and afternoon shifts, to the night shift. The maintenance manager responded that yes, we could likely put the ice plant onto the back shift, as there was usually three days of ice present in the icehouse. The plant manager then asked the maintenance manager how soon he could adjust the pressure on the ammonia compressors supplying refrigerant to the tunnel freezer.

As it was a Tuesday, the maintenance manager said he could probably get this done by Friday. The room was still very quiet. The plant manager responded that as it was 11:30 a.m., possibly the maintenance manager could get the change done before lunch. At this point I believe the maintenance manager started to catch on to the consequences of what had been happening. That afternoon, with higher pressure ammonia, the line was back running with over 1700 pounds per hour.

We had nearly approved an expenditure of $1 million, and a major interruption in production within our plant. This was not the fault of the maintenance manager, as he had been looking after the best interests of the company by avoiding these $10,000 fines. However, this appeared to be an occasion where sharing of information between the different departments was lacking. What we had here was a communication problem.

On my side, I had missed the most obvious question. What determined the speed of the conveyor freezing the portions? It was a matter of the material to be frozen, but then it was also the amount of cold being supplied to that freezer. Remember to always ask why five times or more.

A Communication Story: Timing is Everything

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While monitoring a value-added seafood plant, I noticed that the operators were having a rough time closing the packages of fish sticks. This was a large institutional box of fish sticks, containing about a kilo of the 25gm battered or breaded sticks. When I asked what average weight was going into the box, I was informed of a weight that was dramatically more than the 1 kg mentioned on the exterior of the packaging. I asked why there was so much ‘give away’ in the box? The response was that by law there had to be a set amount of fish in the box, and using a scrape test, the company had determined what total weight of fish sticks had to be in that box in order to meet the regulated fish weight required. The company would monitor the stick weight and flesh percentage several times per shift and adjust the scale weight to reflect that they were meeting the Government regulations for seafood in the overall box.

I pointed out how it would be much better to weigh the sticks earlier in the process, and then shifted my focus up the line to before the freezer to determine what methods were being used. There I noticed the supervisor sampling the fish sticks approximate every half hour. What I came to question was not his method of sampling, but the tools he had at his disposal. The supervisor would pick up 10 sticks, each weighing approximately 25 gm. He would then place them on a large scale to check their weight. The scale was a 25 kg scale, on which the supervisor was attempting to accurately weigh 250gm (1%) of fish sticks.

The supervisor would then record this weight on a piece of scrap paper, and as necessary would move to the front of the line to adjust the batter and breading calibration if an actual adjustment was necessary. I asked the supervisor what they did with this piece of scrap paper at the end of the shift, and they pointed out that they tossed it into the waste bin.

I suggested to the plant manager that we install a simple tool called an X-bar R chart. The plant manager was not very keen on this, but over the course of a day or two I persuaded the individual to at least let me try this as a trial. I also arranged for a smaller digital scale to be set up to replace the 25KG scale.

Now the Plant manager was very insistent that I only try my experiment with the new chart on the day shift. The supervisor of the day shift was also quite enthusiastic about having a clipboard and a document to track his numbers. Additionally, it told him what times to sample the line.

As I said in the title, timing is everything. The day I proposed to show the SPC chart to the day shift supervisor, I found reasons to make myself busy through a large part of the day. Finally, I had the time to take the chart sheet out to the supervisor, late in his shift. As it turns out, by the time I took it to the day shift supervisor, it was also about the same time as the afternoon shift supervisors were showing up in the office. There I am in the office, presenting this new SPC chart to the day shift supervisor, with the two female supervisors from the afternoon shift listening in across the room. Part way through, they came over to me, and asked for a copy of the sheet as well. I made some small mention this was just for the day shift, but here was a copy for them as well if they wanted to play with it that evening.

The next day I was walking into the plant, and the Plant manager came up to me. In a less than pleased voice he points out that we were only supposed to use the test sheet on the day shift. He had heard that the afternoon shift also got access to that sheet. I responded that I had been showing it to the day shift, when the two afternoon supervisors had requested a copy of the form as well. I had attempted to tell the two supervisors that the form was only for day shift, but they had insisted.

At this point the Plant manager stopped, thought for a moment, and then responded “Walter, you probably made a very healthy decision giving them the piece of paper”. We both chuckled, as he recognized that neither of the afternoon supervisors would have accepted me saying no to them having a piece of paper. It was much healthier for me to offer the paper than find myself head-first inside the garbage bin behind the plant.

The next day we had both shifts controlling the final weight into the cartons far more accurately. We were probably saving 50-100gm per carton, and the cartons could fold closed and stack better. The result was a savings of multiple $100K per year, and a better-looking package.

Timing and communication are everything. Sometimes you just need to dangle the hook in front of the right players to get them to take it.

A Productivity Story - Cost Justify that Gyro Freezer

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

One of the plants where I worked early on was a seafood company with a value-added fish processing room. There were multiple processing lines in this room, one of which had a gyro freezer. Another line running fish sticks had no freezer but relied on several blast freezers to cool down the finished product. The slabs of fish would be band sawed and then sliced to fish stick size. They dropped onto a belt and traveled through a batter and breading machine, which then dropped them into a fryer for quick setting of the coatings. The stick is still frozen in the center of this hot fried batter coating, much like the ice cream in baked Alaska desserts.

The fish sticks would exit the fryer, and after a few moments of cooling, would be in the hands of the operators who would gather up 14 of the 25 g sticks and drop them into a 350 g carton. This full carton was placed onto a conveyor, would travel over an inline weighing scale, which would check the actual weight and reject over/under cartons. The carton would then feed through a sealing machine and be presented to a packaging table. An operator at the packaging table would grab six cartons, stacked them into two stacks of three, and drop them into a case. Then repeat the same process for another six cartons, drop them into the case, and push the case into the taping machine. Later he would palletize a few cases at a time.

That would have been the procedure if the company had an inline Gyro freezer there to freeze the fish sticks. However, this line did not have a freezer, so instead the sealed individual cartons were placed onto large baking sheets, slid into a rack on wheels, and these racks were wheeled into a blast freezer. Sometimes a forklift was added to the mix to speed up the movement. The racks spent 12 hours freezing the batter and breading coatings solid (remember that the fish core was frozen). Operators would bring the racks out, knock the cartons onto a table, and stack them into the 12 pack cases. Then an operator would slide the cartons into a case and push it into a taping machine. A lot of double handling, and a lot of opportunity for damage.

Management agreed that a new Gyro freezer would be of interest. However, there was the need for cost justification to prove the value in the savings that were possible. The physical cost of the Gyro freezer at the time, installed and handling the volume necessary on that line, would have been about $1 million. Money was tight, so a return on investment of less than two years was necessary. Just think about that. The equivalent of 45 to 50% compound interest return on your funds. Would we like to have that kind of return on our bank accounts?

So, I was assigned the job of acquiring the data to help with the cost justification. I figured out the labor that was extra. Loading up the trays, later unload the trays, and move the trolleys to and from the blast freezers. I looked at the maintenance on the blast freezers, and the maintenance on the trolleys. I looked at the forklift time, and the number of cartons that were damaged or unsalable during the course of the process. Part way through the study, the quality department approached me and pointed out that I should also do a scrape test on the fish sticks. The warm sticks inside the carton were melting the frozen center, and the moisture was migrating out into the coatings.

Weights and measures requirements stated that officially the stick must be 60% fish flesh to be a fish stick. What this meant was that a 25 g fish stick must have 15 g of actual fish in it, after the scrape test. The interesting point here is that the scrape test is performed on finished goods in inventory, not on the fish stick prior to freezing. An actual verification test might take place on the fish stick days or even weeks after they went through the process line.

This meant that the quality procedures dictated that the fish stick must actually have 17 to 18 g of flesh, so that after the moisture had migrated from the flesh out into the coatings, there was still be 15 g of fish stick weight left. If we were to purchase the Gyro freezer, we would actually need to start with less fish flesh to achieve the 15 gm weight after the scrape test. When I started to run these calculations, it quickly turned out that the savings in flesh weight going into the fish sticks far outweighed any other savings that we were analyzing. A quick series of tests proved that 75% of the cost savings would come from the adjusted weight of the fish in the fish stick.

On top of this, there would be an improvement in the quality of the fish sticks. Less moisture would migrate into the batter and breading coatings. The fish stick would be crisper and give a much better mouth feel to the people consuming it. When the final numbers were presented to management, they were more than enthusiastic for the change and new freezer.

Another interesting offset was the fact that the operators were very happy to adopt the new Gyro freezer. They were bored with the messy work of having to shelve up all the cartons onto the trolleys, and later knock them out and assemble the final packaging. They preferred the continuous flow they could see on the other line in the plant, which was running fish portions through a Gyro freezer. It just made more sense to them, even though it slightly reduced the amount of manpower necessary to do the racking.

A Communication Story - Communication within the Plant

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While working on a value-added seafood line, I notice that the slabs being sliced into fish sticks frequently had a couple of malformed sticks near the end of each slab. After these were breaded and battered, they still looked like stunted or broken fish sticks. These had to be separated by the packing operators. They were placed into large bulk containers and sold under a lesser brand name, which we often called Seafresh. Perfectly good seafood, but not up to the cosmetic standards required by some consumers.

I became interested in why the ends of the slabs were not square and true, as the steel pans the fish was packed into were very square. I walked into the Wet Fish Department, and watched the operators packing the fish fillets into the pans for the plate freezers. The operators would take a pre-weighed amount of fish fillets in a plastic tray, dump the fillets into a large metal freezer pan lined with a waxed carton, and then spread it out to fill the pan. The operators were doing a good job of this, but they were not really pushing the fish into the very corners of the pans.

I asked an operator if she would mind pushing the seafood out into the corners. She came back with a very simple question that brought a smile to my face. Why? I started talking about how these frozen blocks of fish were run through a set of gang saws, and the rounded corners made for poorly shaped fish sticks. The lady then asked where this happened, as she would be interested in seeing the process. I was greatly surprised and asked how long she had been packing fish. She responded with some number like 15 years.

I stepped over to the supervisor and asked if I could borrow the operator for a few minutes to walk down to the other end of the fish plant. I went back to the operator, and we went for a walk of about 75 yards. We passed through two doorways, which separated the wet fish end of the plant from the cooked fish area. The lady waved to several friends as she was walking through the cooked fish area. It was a small town, so everybody knew everyone else in the plant. We walked to the fish stick line, and I showed her how her frozen blocks of seafood were stripped of packaging and run through a series of three band saws to make the slabs.

She quickly realized the problem that existed in having rounded corners on the blocks of seafood that she had been panning for years. We returned to the wet fish end of the plant, and she explained to her colleagues what they had to do, and why they had to do it. She also explained the problem to the supervisor.

I did some calculations on the numbers and pounds of seafood going through that plant. My numbers showed that the walk had saved the company about $75,000 per year. She had been working there for 15 years, had never been into the other areas of the plant.

It always surprises me, how people can work in a company for many years and have never been given the opportunity of going through the entire facility to determine how it operates. As with many things in operations, the outside pair of eyes frequently contributed far more than would be expected.

Another point of weakness for many companies is the receptionist. The first point of contact for many companies, and this individual is usually the least knowledgeable or the most recently hired. Even companies that are business savvy enough to have a live operator answering the phone, frequently put the least experienced person on their phone.

A Communication Story - Just How Many Did We Order

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

I noticed some disparity between the quantities of seafood Toronto was ordering, and what the plant was producing. It took a while to follow through, but eventually I determined where some of the issues were.

Toronto sales would see a reduction in the warehouse stock, and would order up a thousand cases of product X.

The order would flow to the Halifax office, who would add a bit of a buffer to the order, making the order 1100 cases of product X. This would then be faxed to the plant in Lunenburg, where the office there was doing the actual production scheduling. They knew that the machines in question could run 1200 cases between start up and the first break. So, they would change the order to 1200 cases, and add to the schedule for several days hence.

The truth was the production line had gotten even more efficient and was running just over 1300 cases between start and first break. The result was we had grown our order from what marketing had requested by about 30%. Not a problem if you are moving the volume quickly, or running products on a weekly basis, but a problem for certain species of fish that were only being processed three or four times per year.

The problem with frozen seafood is that you really need to consume it within about six months of it being processed. Otherwise there is plenty of chance for freezer burn when the fats and oils within the seafood go rancid. You must remember that a normal freezer does not give you the low temperatures you need for long-term preservation of seafood. Enzymatic activity does not stop when seafood is frozen, but just slows down at the temperatures present within a residential freezer. If you really want to keep seafood frozen and in good quality, you need to be talking temperatures like minus 40 degrees, where both the Fahrenheit and Centigrade scales meet.