Operational Excellence

A Productivity Story - The Automatic Bagging Machine

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

One of the first posts I was assigned to study in the Tampa shrimp plant was the multi-head automatic weigher. This machine was stacked vertically over a form-fill-and-seal bagging machine. The weighing scale could process several tons of shrimp per hour. The machine was set up to weigh 5-pound bags of shrimp, and it could fill one of these bags every five seconds or so. Across from the machine was a manual filling post. The manual filling post had 4 or 5 workers, who were scooping frozen shrimp into 8-ounce bags. They would open the bag, scoop up some shrimp, stand the bag up on a scale, and then add or delete shrimp to make the 8 ounces. The full bag of shrimp was then placed in a tray, and when the tray was full, it was transferred to a sealing post.

The sealing post operator would pick up a bag and pass it through an automatic bag sealer to another operator. The second operator would then pick up the sealed bag and pack them 10 or more to a case, depending on the desired case pack.

I stood watching the manual process, and then turned and watched the fully automatic machine. I could not figure out why we were making the ladies suffer with the small bags on the small weigh scales. I asked if there was a filler head for the small size of bags. I was told that the machine did have a range of head sizes, and they did have the flat stock plastic to run on the different head sizes. However, the company was after filling large bags at high speed, as it helped to keep the reported poundage up on the machinery.

I did some calculations for the company and showed them that it would be more cost effective to hand fill a 5-pound bag and machine fill the smaller 8-ounce bags. The plant managers had a rough time accepting this but agreed to doing a test for a day or two. The multi-head weigher and automatic vertical form and bag sealer were quite capable of handling the 8-ounce bags. On the other hand, the manual operators were more than happy to work with the 5 pound bags, as they were easier to open, could use a bigger scoop to fill, and didn't tend to fall over on the larger weigh scale platform. We lost some speed on the manual 5-pound bags, but this was more than compensated for by the 8 ounce bags that were flying out of the multi-head weigher.

One would think that the labour saving was a critical aspect of the process just described. However, it paled in comparison to the savings on give-away that had been occurring in this process. Give-away is when the manufacturer puts more product in the bag than is specified on the label. How much had we been giving away, and why had we been giving it away?

At this point we need to have a short lesson on statistics. When filling the 8-ounce bag, the average give-away is half a shrimp. How can I say this without supplying any supporting numbers? Very simply. A portion of the time the operator filling the bag would put in a scoop full of shrimp and might end up with the correct weight in the bag. This was a well filled bag, with no give-away, that management and inspectors would be happy with. At the same time, it was just as likely that the contents of the bag might be 1 gram short of the label amount. This would necessitate adding an entire extra shrimp, which would result in a lot of give-away. You can see where I am going, and how we got to the half shrimp of give-away.

Now let us look at the automatic weigh and bag filling machine. At the top of the machine is the multi-head weigher. In our case I believe it had 14 individual weighing heads. The shrimp were dumped onto the center of the circular platform, and individual vibrators would move the shrimp out onto their respective load cell pockets which surrounded this platform. The system would vibrate until each of the load cells had one quarter to one third of the final weight they were looking for, according to the bag weight. The computer would then quickly analyze the weights on the 14 individual scales and determine which combination of three or four of those scales would give the best weight to go into the bag. A few calculations show that there are approximate 6000 choices of scale combinations to make the correct weight. The computer can do this in a few tenths of a second, and then dump the appropriate three or four scales down their chutes, where they combine into the single bag.

Good machinery can do this at 60 bags per minute, or even as fast as 200. In some cases, the vertical form, fill and seal of the bags cannot keep up with the weigh scales, and the machine has two bagging machines underneath it. This multi-head weigher can give you consistent accuracy with less than 1 gram of overweight.

What did this mean for the 5-pound bag? The customer was getting 5 pounds of shrimp, with no giveaway. On the other hand, the 8-ounce bag had an average of half a shrimp of giveaway. A 5-pound bag weighs the same as ten 8-ounce bags, so manually filling the small bags, we were giving away five shrimp equivalents. Meanwhile, packing the 5-pound bags on the big multi-head, we were giving away nothing. Let us reverse the system now and filling the 8-ounce bags automatically gave away virtually nothing. Only the manual 5-pound bags were giving away about ½ shrimp per bag. You can see the savings. Five shrimp minus one half shrimp is equal to 4.5 shrimp savings per 5-pound bag. We do not even need to calculate what size the shrimp were, the savings will be there every time.

The savings in labour, and a far greater savings in give-away, represented several hundred thousand dollars per year to the company. And this occurred while making the job easier and more pleasant for the operators.

A Productivity Story - Plant Efficiency from New Technology

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

I was working in the Industrial engineering department at a tire plant. The maintenance department had identified the need to speed up the preventative maintenance being done on the massive two-story presses that cured the tires. At this time, the work required two operators, working on different floors, having to coordinate the adjustments and changes being done on the machine during the servicing. Maintenance had recommended they try out some new walkie talkie style radios, which were equipped with headsets. These were rudimentary pieces of equipment at the time but could be worn by operators and would stay on their heads.

We were doing standard time-study on the operators. A colleague had analyzed the work process the previous week, without the use of headsets. I did the timing the subsequent week, with two operators having the headsets to assist them in the teamwork aspects of the job they were doing. The results were quite dramatic, with the operators finishing the process in two thirds of the time. The operators were able to adjust parts and movement heights for the press, without having the to yell through the narrow opening in the concrete floor around the press. They were calm, relaxed, and working along well together, and still able to joke with each other.

This is a classic example of technology, even though rather simple and ordinary, helping to vastly improve the speed at which the team can work on the project. This is especially valuable in noisy environments, or places where the operators are a fair distance from each other.

A Productivity Story - Listen to the Production Floor

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Frequently when I am walking around the production floor with the management staff, I will stop and ask them to look at a process. While they are looking at the process, I will ask them what they hear. This usually brings a frown to their faces, as they are trying to decide whether I just made a mistake in my words. Did, I mean to ask the question, what do you see? Or am I really asking the question, what do you hear?

I am asking the clients, what do they hear? To be more precise, I am really asking them, “Do they hear any manufacturing taking place?” I will point out, while looking around, that we see no operators sitting in a comfortable lawn chair with a nice mixed drink in their hands. But at the same time, the workers are not doing any value-added work. I will not always claim that the sound of work taking place is value-added work, but at least you can hear something taking place.

Can you hear the tools being used, can you hear the compressor powering up the paint sprayer, or are we just listening to air leaking from the compressor lines? Is a fastener gun being used, is a machine filling an item, is the operator banging parts into place? If you do not hear work being done, then trust me, nothing is being done! And though we can point out that frequently the operators are thinking about something, the truth is that most thought processes occur instantly. Also, they can usually think as they are walking. On the other hand, texting and cell phones often make a lie of this, especially when the individual is wandering around in traffic.

When I was a manager at a bottling plant, I always kept a foot on the floor. Through the vibration of the floor, I could tell when the canning machine was operating. And when it was operating, it was producing several hundred cans per minute. When the floor stop shaking, I was not producing any cans of pop. And that is not a situation you want to be in, especially on a hot summer day. When the floor stopped vibrating, I was on my way to the can line to see what the problem was.

A Productivity Story - How Much Off-cut is Normal

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

In a rubber extrusion facility, they were extruding lengths of rubber products. While using these products in the next set of processes, offcuts were left at the end of each reel. These offcuts were recycled within the plant and brought back as new product to be used in the next production run. Historically the offcuts were about 7%. This was a reasonable percentage, and everyone worked around this number with their monthly measurements, rising or falling in relation to that percentage.

At some point, an individual realized that the next step in the plant process had very specific lengths being consumed from these extrusions. The suggestion went out to measure the amount of extrusion being put onto each of the large reels in relation to the units of consumption in the next shop This was quite simple to do as the extrusion apartment had counters tracking the number of meters of material on each reel. The operators began cutting the material in relation to an integer multiple of the consumption in the next shop. Within days, the extrusion shop was seeing a massive reduction in off-cuts coming back for recycling. The percentage of offcuts dropped from approximately 7% to a new number of around 3%. This was a massive amount of material not having to be handled and recycled back into the system.

A Productivity Story - Determining the Batch Size

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

When visiting a new client one of my favorite tricks is to determine their batch size before we leave the office. I ask the client what the footprint of the product is and then I divide this number into 32. Sometimes I divide into 16 depending how large and heavy the product is. A client asked me where I got that 32 from, and I point out that is a 4x8 sheet of plywood used to make inexpensive work benches for production. When the company started, they could not afford expensive work surfaces, so they took sheets of plywood and added legs.

It is surprising how many times I am correct with this foolish little calculation. Many clients are trying to save money and operate under the mistaken belief that is far easier to process a batch of goods instead of single piece flow. Operators also have the idea that it is better to do the job many times in a row, rather than doing sequences of jobs. This is a very mistaken philosophy on a variety of fronts.

On the quality front, there is the risk that the operator will make a mistake. This generates a whole batch of defective parts or assemblies, before the next manufacturing step has a chance to catch these errors. This can happen when an operator is measuring a cut length, and then cutting a whole batch of pieces to the same length. If they made any mistake in their first piece or the verification of it, then they have a pile of scrap at their disposal. A mistake can be the machine starting to wander in tolerance over time. If this is the case, then there are simple tools to verify if the machine is still in tolerance, or call maintenance to re-tune the machine. But the key here is to not make a whole bunch of scrap, when you suffer from the illusion that it is more efficient to do the same job a bunch of times, rather than in a sequence of steps.

On the production front, having a batch that is moving through the plant takes material, manpower, and generally slows down the flow through the plant. Flow manufacturing with single piece flow or just-in-time, are some of your most powerful tools and are frequently abused or not used at all. I often use the example of a batch of cookies to explain the concept to the people I am working with. Everybody understands what a batch of cookie dough is, as we have seen them since we were tall enough to look over the counter at mom making us cookies. Batch is a simple concept to work with. Well, it is a good idea, but you must recognize that a batch of cookies is not really a batch of cookies. The batch of cookies is one bowl of cookie mix. Whether you decide to make a single cookie 3 feet in diameter, or a hundred cookies 3 inches in diameter, is all up to what you are trying to do to satisfy your customer. Of course, there is that little limitation about the size of your pan and the size of your oven door.

Another issue with having a 4x8 workbench is that it frequently separates the operators around the shop, and virtually eliminates the opportunity to have a manufacturing cell. How far apart do the workers need to be? This is a statement that I pose to all the manufacturing companies that I visit. Some have large items that need enough room for the item to move around between the operations, so the operators might be 10 or 15 feet apart on the line. Without question, if the item is that big, several people can be working on it at the same time, and it is totally unnecessary to have the workstations far apart. I point out to clients that workers only need to social distancing apart. They should not be any closer, or they may be regretting the Caesar salad that their colleague had for lunch. On the other hand, if they are more than 7 feet apart, how can they move to help the colleague if they get behind in the job they are doing. I frequent tell my clients to place the workers at just over handshaking distance from each other, so they can pass the part that they are working on from one to the other or from one station to the other or between the stations. It is usually only necessary to have stock for one or two pieces that are in progress. If you have more stock than that, you are creating a buffer, and offering the other workers the opportunity to process the units out of sequence to how they should be processed.

I was recently at a large plant of 200,000 ft.². There were a lot of workers in the plant, but if you consider that the average worker needs about 10 ft.² to work in, the workforce was only occupying 1% of the plant floor. From what I could see in my tour, it appeared that the workers were spending half their time moving materials from post to post. This is not a profitable use of their time, and if anything distracts them from the primary function of manufacturing the item.

A Productivity Story - The Tennis Court as a Production Tool

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

I remember listening to a lecture once by a Venture Capitalist. He reminded the engineers present of a common tool of how to keep floorspace clear, after you have thrown out all the junk and shrunk the production process. With some companies, the open area is reclaimed for a ping-pong table, or some other piece of lunchtime sports equipment. This keeps new material, and other such things from creeping back into the area. Employees do not want to give up their sports equipment. They will make sure that the other things find some other home or get processed as they should be and shipped from the plant.

In this case, the engineer was working on a large plant and was freeing up a lot of floor space after the first few ping-pong tables. He found he had more space than he needed for the ping-pong tables, so he moved up to the next size of recreational area, the basketball court. A couple of basketball net stands purchased from Costco was enough to use up a fair amount of space. However, as they were making some real inroads into plant usage, he quickly got to the position where he had more basketball courts than he had teams of employees to play on them. If you really want to chew up empty plant floor space, you need to be using the tennis court I suppose he could have moved on to a floor hockey and other such ring sizes, but the point has been made here.

The other solution is to put up some walls, and sublet the excess space in the short term, in the hope that marketing will increase the demand from production in the coming years. This of course depends on the local market.

A Productivity Story - The Preportioner Machine

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

In the factory fish sticks are made by using gang saws to cut slabs from fish blocks. These are then fed to a slicer, which rapidly slices the long slab into the stick shape. The issue from a productivity point of view is the amount of sawdust created during this process. The sawdust ended up just being washed away into the drains. An American company recognized the opportunity in any industry processing blocks or materials that had to go through band saws. They created a machine called a preportioner, which was much the same as a junior version of a log splitter. Another analogy is a slicer through which potatoes pass at high speed to make French fries. I calculated the cost justification for purchasing it by calculating the loss on the sawdust, and the maintenance on the band saws. I quickly came to the conclusion that using a preportioner in combination with the existing tempering of fish blocks delivered a sizable improvement of the yield from the 16.5- and 18.5-pound fish blocks.

While going to visit the preportioner manufacturer, I had the opportunity to travel to a French fry plant. This generated several novel stories and situations. The first was an interesting quality machine. It was optically scanning a wide bed of French fries looking for potato eyes. This material and some surrounding it would then be ejected by an air gun and reused to make potato products.

The potato company also told me an interesting story about a recent remodel they had done. As there is a low percentage profit on French fries, they cannot afford to have the plant down for very long. They determined with the work of the contractors that the entire remodel could take place over the course of a week. The deconstruction of some equipment and the removal of some concrete proceeded on schedule. It was then time for the electoral contractor to install conduit underneath the slab. The contractor was doing well but was slightly behind schedule. When it came to the point in time for concrete pour of the new slab, the electrical work for in the slab was not completed. The electrical contractor apologized profusely to the company and the engineering staff, saying they would be ready for them in two or three hours. The company responded, that was fine, the concrete pour would start at the other end of the plant and work towards the incomplete section. None of the other contractors seemed to get behind schedule in meeting the requirements from that point on.

A Productivity Story - The Garment Industry

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Years ago, I was visiting a local high-end garment company. They made a high-quality product that they can sell with a high price point in the international market. Our group went for a tour of the facility, and watched them during the counting, sewing and other processes necessary to make the garment. In the end we were shown a massive warehouse that took up nearly half of the company floor space and was filled with garments and inventory waiting to leave for various client retail locations. We returned to the boardroom and started discussions. As any good manager knows, make sure you have the answer before you ask the question.

My first question to the general manager of the company was “how long did it take the garment?” The general manager responded with a smile that there were timers on the sewing machines, and it took about a hundred person minutes to sew the garment completely. My next question was “how long did it take from where the material was first on the cutting tables, to the garment finally being finished and hanging in the warehouse?” The general manager responded with “anywhere from four to six weeks, depending on the time of year and backlog of orders.”

I proceeded to put my foot in my mouth by saying to the individual, “So you’re telling me you took an hour and a half job and stretched it out to six weeks”. The general management was rather offended by this statement, and responded in a rather heated voice, “Listen, the customer only orders four times per year.” Well in for a penny, in for a pound. So, I responded rather flippantly, “No. Number one, you set up your costing structure, so clients are incentivized to only order four times per year, otherwise the garment is way too expensive. Then you change over to the next season, so the clients cannot refill stock as it is consumed during the season. Finally, at the end of the season, you do not take back any excess stock from your clients and customers, but rather leave it with them. And then to add insult to injury, you change the style and the colors for the next year, so any stock they are left holding is quite obviously last season’s stock.” Therefore we see so many companies selling off the remaining inventory at half-price at the end of season, in that they know if they keep it for another season, they will not be able to get much money for it.

In this case the meeting ended soon after, and for some reason we were not invited back. The sad truth of it is that this was a Canadian manufacturer, and a year or two later I remember reading about how they had to run off to China due to the high cost of Canadian Labour. Well, the fact of it was that Canadian labour really was not very expensive. Their problem was that most of the time the workers that were supposed to be sewing, were instead moving product around the facility.

A classic example of the craziness of this manufacturing, was the initial cutting of material to make up the garment. Several individuals working across several tables would cut up multiple layers of the material to start making the garment. Then a very experienced person would pick out the bits for the right sleeve, the pieces for the left sleeve, the pieces for the right torso, etc. They would take all these pieces and stuff them in a bag and hang the bag on the monorail that moved between the cutting room and the sewing room. The bag would take several days to travel to this next destination. In the sewing machine and individual would dump the bag out and start to sort the pieces for their job. If they were doing sleeves, they would pick up the pieces for the left sleeve and then pick up the pieces for the right sleeve. They would sew the two sleeves, then throw them with the rest of the pieces back into the bag. You can start to see what is wrong with this.

Once you identify a piece, do not put it down until you finish the work on it. A solution to the problem would have the experienced person selecting the pieces at the cutting table and passes them as groups directly to the sewers. As soon as they picked up the pieces for the right sleeve, they would hand it off to sewing operator, then pick up the pieces for the left sleeve and hand them off to another sewing machine, then the pieces for the right front torso, then the left front torso than the back, each being given off to another sewing machine. When these sewing machines finish their parts, they would feed them over to the individual who would integrate them into the finished garment. The result would be that 15 to 20 minutes after the material was cut, the garment was finished. No time would have been lost with people continuously trying to sort through pieces of material. Time after time, we see parts travelling through without labels, and people are constantly having to look at the paperwork to see what they are working on.

A Productivity Story - Value Stream Mapping

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Years ago, I was touring a local aerospace company as part of an Innovation Insight tour, organized between IRAP and the CME. We had an excellent tour, and afterwards were sitting in the boardroom discussing different procedures and concepts. The manager who had taken us on the tour asked if the group knew what a value stream map was. This was the first time I had heard of this tool, and after watching him explain it, pointed out that this tool was just a process map with the different processes tracked across time. The manager corrected me and pointed out that it was a far more valuable tool than the process map, as it included time factors into the overall presentation, and separated value-added from regular functions.

The manager went on to explain how they had used the tool when they come across a case where they had not been able to supply a certain part, quickly enough to the customer. With the value stream map, they determined that the part was taking 28 days to travel through the plant. During those 28 days, their team calculated they had performed 14 minutes worth of value-added work on the product. As this was an aerospace part, very few attendees were surprised and made the general comment that the time taken reflected all the certifications on the part. The manager quickly corrected this assumption. When the aerospace management team took a closer look at the flow of the part through the plant, they realized that very few of the items listed on the chart were associated with aerospace certification. Many of the steps were internal procedures and requirements that had nothing to do with certification.

After looking at the value stream chart again, they realized that many of these internal procedures were not even necessary anymore. Some of procedures were so out-of-date, they could not remember who had implemented them, or why they had been implemented in the first place. With some judicious agreements around the table, many of these ancient procedures were tossed out. At the end of the discussion, the time flow through the plant was eight days, with still the original 14 minutes worth of work. The aerospace company was absolutely blown away by what had happened with the revision of this process. From a cost-benefit point of view, the alternative on the table had been the purchase of a million-dollar machine cell to help improve the productivity of the item in question. As it turned out, the manufacturing productivity was not the problem, it was the paperwork procedures associated with the process that were holding them back.

It is stories such as this that has shown me what a valuable tool the value stream map is. I have presented the tool and shown companies how to use it many times over the years. Integrating a tool such as this, with a strategic tool such as Theory of Constraints, gives the industrial engineer a very powerful toolbox for analysis and solutions. It shows us where to start, rather than just grabbing at all the low hanging opportunities for improvements.

A Productivity Story - Sequencing the Production

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

At Coca-Cola one of the things we liked to plan was a daily production schedule around a fairly set sequence of flavor changes. As machinery was cleaned every night, and often several times during the day, we started the morning with a clear beverage. The next flavor to follow was something usually darker, such as classic Coke. The reasoning behind this was that if there was any material still left in the machinery, it was better to have the dark following the light, where you could not see the lightness in the dark product, as versus having darkness in a clear product. You always set a production run-up so that even if there was a slight mistake in the system, this would not result in a defective product. You also set up the end of the day with a complicated product that might have oils requiring special sanitization, so we would not tie up valuable production time during the day doing long sanitation cycles. The long sanitization cycles were kept for the evening. It's all about setting up your production system to run in the optimum method and externalizing the sanitation for the back shift when most of the crews have gone home.

A Productivity Story - Recycling the Cardboard Boxes

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While working for a bottling company, I had a machine that needed repairs on one of my lines. I called the local service tech, and he was able to do the repairs and get the machine up and running again. In the end he noted the stacked collapsed cardboard boxes heading out to the recycling bin and asked if his son could have some. I said I was happy to give away a bunch, and how many did he want? The technician replied that his son was starting a moving business and would like to buy as many of the boxes as I could supply. I asked the technician to have his son discuss it with me as I felt we could come to a simple arrangement. The young man showed up and told me that he was getting into the business of selling moving boxes. He was sourcing used boxes of good quality from several different companies. Then using brown paper tape to cover up the appropriate logos that might give away the source and selling them for a few dollars to people who were moving.

We determined which of the boxes were the best quality and the greatest volume. He supplied some metal trolleys with wheels and placed them near where the boxes were normally collapsed down onto a pallet for later evacuation to the recycling bin. The operators of the line were informed what was happening, and happily agreed to start filling the trolleys. About a week later the young man turned up with a van and came in to roll the trolleys out to his van and unload the cardboard. He asked if I wanted to count the cardboard, and I said I was more than happy to settle for $.50 per case that he was offering, and felt no need to audit what he was doing.

This arrangement went on for several months, and with luck is still going on today. Now I need you to recognize is this is not just a good green recycling story. There were several other factors in play here. First the plant had a strong union, and a union member was losing part of their job. But the union members were more than happy to give up this job. No one liked hauling a pallet of cardboard out the recycling bin, then standing out in the dark of a cold loading dock and pressing the button to run the compactor, to compress the cardboard into the cardboard recycling bin. For safety reasons the button had to be held for the full cycle to be sure that operator was not being caught or injured in the process. The union members were more than happy to give up this unpleasant task in support of the re-use of the boxes.

Another factor that most did not notice, but I was very aware of, was that the wooden pallet of stacked cardboard needed to be carried up a narrow aisle that fell between two high-speed bottling lines. To access the wooden pallet, a forklift was used to drive up the aisle, pick up the pallet that the cardboard sat on, and back out to begin the trip to the recycling bin. Several times a shift, this large ungainly forklift would drive down this narrow aisle way to pick up this pallet. Instead, I now had the operators once or twice a week walking the trolley out through these two high-speed lines. If a forklift had made any mistakes, it would have hit one of the conveyors and probably shut it down for several days while we tried to get it straightened up and realigned. We had put a new process in place that eliminated a rather difficult but not dangerous forklift function. We had improved the quality and the safety of the shop, while helping our company make more money on reuse than the company was getting for the corrugated cardboard going in the recycling bin.

A Productivity Story - The Seafood Scoop

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

The seafood plant I was working at had a tray product of seafood and rice with a sauce covering. We came across an interesting problem with a new dish. The new product was supposed to have tuna fish in it, and an interesting question arose as how to portion the tuna fish in the correct amount. With seafood portions before, we just put a square of seafood in the tray of the appropriate size and weight. The tuna fish arrived in large 48-ounce cans, and we needed to determine how to dispense it.

I was given the job of trying to figure out how to measure the portion size. This line was running 30 trays per minute, so the operators did not have much time to get the correct amount of material into a scoop, and then deposited in the tray. I tried a variety of measuring cups, ice cream scoops. spoons and various other techniques. We came back to an oversized tablespoon, and a little warm-up by the operators first thing in the morning. They put a bowl on a scale and tared the weight that was required. They then practiced several scoops until the got the weight and volume correct. We found out that within a minute they were warmed up to what the volume should be, and consistently could scoop with a tablespoon the appropriate number of grams of tuna fish.

What this story says is that often the simplest solution is the best solution. People know to look at something, then estimate the volume and size. Given some way to cross check the numbers was all that was necessary. This simple manual technique may be replaced with a machine at some point in the future, but I would claim they would be hard put to cost-effectively implement a machine to replace an experienced operator who was comfortably seated at their post.

A Productivity Story - Warehouse Storing Junk

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

In the early 90s I became the purchasing manager for a multinational company. I was working in Halifax at the time, and the company had a major temperature-controlled warehouse in downtown Halifax. You must realize that this is the most expensive real estate east of Montréal, and the space was in a high rent district. I had been to visit the warehouse once or twice, just stopping in the office and talking to the operators. One day it was raining outside, and I decided to access the warehouse through the back door, for which I had a key. The back door was far closer to my office than the loading dock. I unlocked the door, went inside and as the door closed behind me quickly realized that I could not see a light switch anywhere. I again opened the door and checked the walls around the entry, but there was no light switch, and the warehouse was dark. As it was still raining heavily outside, I decided to use the toe radar to slowly feel my way forward into the warehouse, using the small amount of illumination from the emergency exit lights.

I finally got to a row where I could see down one of the aisles towards the lighted interior, and so just walked down the center of the aisle towards the light. When I got to the office, I made a joke about whether I had forgotten to pay the electrical bill that month. I said this with a smile on my face, expecting some joking replies. The response was an interesting comment. We seldom turn the lights on back there as we don't need anything in that area”. The next light that went on was the one in my head. I immediately asked him to turn on the lights, and we would go for a tour. This is one of my favorite stories about what I found in those dark corners of the warehouse.

Stored in the racks were pallets of sacrificial zinc anodes, which would spend their short lives on the bottom of the vessels fishing in the North Atlantic. Additionally, there were pallets of massive three-inch Samson braid deck line, also being stored in temperature-controlled splendor. We then moved on to other racks, where I saw dozens of pallets of monolingual English fish packaging. As Canada had demanded multilingual packaging for many years now, I knew these items had to be nearly 10 years old. Even aside from this knowledge, the dust on the surface of the boxes gave away this fact. Checking the titles on the boxes, I came across some names of fish species which I did not know, even after having been in the seafood industry for several years now. Being a good Maritimer, I additionally had more than 30 years of knowledge of the many species of fish caught in the North Atlantic.

Getting a print-out of the inventory, I returned to my office and started doing some calculations. In the end, as I remember the rough numbers nearly 20 years later, there was $6 million of inventory in that warehouse, but only $2 million of was usable product. Additionally, of that $2 million, only $400,000 was moving in what we could reasonably call a rotational basis. Some of the usable items in the warehouse were too far away from the customer to be of adequate use to the customer. When a fishing vessel comes into port, that ship must be turned around in 48 hours. This often meant that there was insufficient time to order the product from Halifax, so instead the items were ordered from the local ship chandler in the village or town where the vessel docked.

This then raised the question of what we should do with the rest of the product. As no one was willing to admit they had made a mistake in over-ordering items, I came up with a reasonable solution of charging $.50 per pallet per month for any items that were in the warehouse more than three months. There were a lot of complaints from different managers, but my manager supported the decision and pointed out politely that the other players would just have to take their lumps and show their dirty laundry to the directors of the company. In the end it took a full company directors meeting to admit that the assets present in that warehouse were mostly fictitious, and in reality, represented a cost to the company to dispose, or recycle, the materials.

A Productivity Story - How to Stop the Evaporation of Wine

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While working in a seafood plant, I came across a couple of novel ways that the company improved productivity and stopped or reduced losses. The sauce room contains large kettles with steam jackets that were used to make the various sauces for the tray products on the line. Mixing up the kettle of sauce was fairly simple. Two primary issues came up mixing the sauces, and the recipes were adjusted to reflect these. First was they used large 48-ounce cans of tomato sauce that were added to the kettle. It would have been foolish to save partial cans of product, so the sauce mixes were adjusted so that there was an integer number of can used. This means that the recipes were adjusted to use a whole number of cans, say 10. The spices were then adjusted to meet this percentage, as in say a 10.2 pound bag of spice, whatever was necessary for the volume in the sauce. The variable then was the water that was added through a very accurate flow gauge. The volume wanted was dialed in and the correct amount of water was being added to the kettle.

An additional advantage of this was that anybody walking into the kitchen could quickly see that the correct number of cans had been opened, and only one bag of spice had been used. This is a good crosscheck for operators in the sauce room, and they could check the other person's work without being obvious.

Another interesting item was that some of the sauce recipes involved wine. For one reason or another it was found that there seemed to be high rates of evaporation of the wine being stored upstairs in the warehouse. By this I mean that when a case of wine was opened, sometimes we found that the 1 gallon jug of wine was actually not full anymore. We could put the room under better security keys and cameras, but a far simpler solution presented itself in the recipe. The recipe called for a fair amount of salt for the taste profile. The company making the wine was contacted, and they agreed to add the appropriate portions of salt to the wine for the recipe being made. It is amazing that after this salty wine started showing up in the warehouse, evaporation rates dropped off by a hundred percent. There was never an empty bottle after this point in time, as the wine was undrinkable until after it was diluted across 100 gallons of sauce.

As you can see, there are usually a variety of ways to solve quality problems and other issues that do not involve confronting people or being obvious that you are checking the quality of their work. Many of these things fall under visual manufacturing, which is a system wherein you check what you are doing, and it is obvious what you are trying to do is correct. Visual manufacturing can be squares on the floor, the shadow board on the wall for broom and dustpan, a rack that holds a set number of screwdrivers, and a variety of other techniques. The key is making it easy for everyone to know what things should be where, and whether they are there, and if they are not there to know where to go looking for them.

A Productivity Story - Eliminate the Wooden Box

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

I was visiting a company on the West Coast that made a product for under the front hood of large trucks. The product was heavy, and about the size of a loaf bread. The shipping box needed a couple of quarts of oil, a controller, belts, and mounting hardware. Historically the company had used a small wooden pallet with thin plywood case affixed to it. The operators would pick the appropriate parts and brackets, place them in the case and surround the contents with Styrofoam peanuts. When they were finished, they would mail a wooden top on the case and attach the appropriate documentation to the wood, usually needing a stapler as tape would not stick to the plywood.

The owner of the company complained to me about the number of customer complaints due to missing items, parts that the customer claimed had been damaged in shipment, or other such problems. My first observation of the operators packing materials was that they were running a batch operation and would go through and place one item in each of the cases before going back and adding the next part to the cases. My issue with this was that breaks, phone calls, and other things broke up the focus of person, and if there were Styrofoam peanuts in the case already, the operator frequently could not remember where they had stopped, and should therefore restart their filling operation.

The owner had another issue as well. His customers were complaining that they can no longer dispose of the wooden box and Styrofoam peanuts. The local cities and municipalities were no longer accepting these materials. Additionally, there was not enough of these materials to justify a separate recycling stream being formed. My contact asked me if I had any suggestions.

I suggested the company switch to a heavy gauge cardboard box. This could easily be collapsed afterwards and put into standard cardboard recycling bins which can be found behind any major business or store. The operator questioned whether the material was strong enough, but I pointed out that there were local suppliers he could talk to. I sent an intro to a local cardboard converter. I found out a couple months later that the introduced company had been in to supply my client with an excellent cardboard box. Inside the cardboard box was another sheet of cardboard with cut-outs that the operators could place the various parts and materials into. The advantage of this was that there was no longer any question of whether all the parts and instructions were in the box, as they were all easily visible and if there was anything missing, it was obvious. The box was a white oyster board, and the customers now made the comment that it felt more like they were opening a Christmas present, not just an old wooden crate that they used to work with. My client was mildly bothered by the increased price of the cardboard over the wooden crate, with the difference being about $1.50 at the time, but he was more than satisfied that this was paid for by the reduction in calls for lost and missing parts. Several years later I was visiting the cardboard company and had a chance to meet the same client during the tour. He had an interesting footnote to add to his story about the improved cardboard box.

It turns out that when his clients were installing his product, they found that putting the exposed pieces in the box in the correct sequence resulted in increased speed of installation by an hour and a half. As the item was going under the hood of a large truck, inside and automotive repair center, this was rather expensive and valuable time that was being saved. One might say that that $1.50 extra cost of the box, saved the customer $150 of work time on the shop floor. On top of that was the additional savings of the reduced call backs and customer complaints when they could not find parts in the Styrofoam peanuts. Sometimes you need to look beyond what you deal with and determine not just what is best for your company, but more importantly what is best for your customer. That is frequently where the greatest profit can be found.

A Productivity Story - Pollock Fillets Deep Skinning Machine

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

At a certain point in the late 1980s, the seafood plant I was working at became interested in how to take a fat layer off Pollock fillets. At the time, codfish was slowly decreasing in volume, and was being replaced with Alaska Pollock. Most of the fillet from the pollock is a large, white flake fillet. However, near the surface of the skin, there is usually found a dark fat layer. Many people find the fat layer to be unappealing, so marketing requested we find a way to remove it and leave the nice white flakes of the rest of the pollock fillet.

The best way to do this is with a machine called a deep skinning machine. This device uses a refrigerated drum to freeze one side of the fillet to the drum. A band saw knife then slices off the fat layer, leaving a very presentable white fillet. A scraper on the bottom of the machine cleans the drum and drops the fat layer into a basket. This basket of material is then blended with other materials to make a very presentable fish block of this product.

The white fillets are then cut into portions, and individually quick frozen into the loins, center cuts, and tails that food service customers wanted. The company was aware that the skinning machine would do the job that was requested. The problem was that funds were tight, and it was hard to get capital purchases past the board. The company wanted to know what type of return on investment there would be from their capital expenditure, but this required data that could only come from testing of our proposed process on the machine.

Fortunately, there was an upcoming tradeshow in Boston, with a display that included the deep skinning machine being put on by the European manufacturer. The manufacturer was based in Scandinavia, so the display equipment would be crossing the Atlantic. I contacted the manufacturer, who had a long-term relationship with our company, and discussed the possibility of the machine stopping at my plant in Nova Scotia, on the way back to Europe after the Boston seafood show.

The manufacture was more than agreeable, provided I would pay for the extra transportation and guarantee that the machine would be well looked after. We arranged for the machine to be shipped from Boston to Nova Scotia after the seafood show. A day or two of installation on the production floor, and the machine was set up for the test. Within an hour or two, we had machine processing fillets and delivering a superb product, to the delight of management and the operators on the shop floor.

With a couple of weeks of data, I was quickly able to prove that the cost justification for the machine would show a payback of a month. By the time the report got to the board, the machine had paid for itself. The Scandinavian supplier was more than happy to sell us the machine that had been demonstrated in our plant. We did request that they keep the actual product and fish species secret for a while, so we could make some inroads in the marketplace before competitors found out.A Productivity Story - Swelling the Product

Hi folks, I am Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

What many people do not realize is that the food industry loves to sell water. This water can take several formats. It can be the water inside a fish fillet, butter, chicken, turkey, or that nice plump watermelon. When you purchase these products, and let the water dry out of them, it is amazing how little material you are left with.

In some cases, as with chicken fillets and fish, injection is often used to keep the items plump. The injectors for these products often looked like a machine from medieval times, with dozens of long needles projecting down from a dispenser. But what do you do when you want to swell a small product such as a small fillets or shrimp? You can keep the product immersed in water, so it does not have a chance to dry out, or you can even add some salt to the water so that the fillets draw the liquid into them by osmotic pressure.

While visiting a shrimp plant, I noticed how the room thawing out the frozen blocks of shrimp (coming from offshore), seemed to be processing a smaller size of shrimp than was ordered for the next phase of the process. If the next day called for 10-15 count shrimp, it always seemed that they were thawing 15-20 count shrimp in the tempering room. When I asked about this, I found out the tanks they were tempering the frozen blocks of shrimp in contained a mild salt solution, and this allowed the shrimp to swell up into the new count range.

This went along fine for several months, until suddenly one day production had to scramble, as the latest batch of shrimp had not swollen in size. Over the next two days, the company quickly came to realize that the shrimp were no longer swelling as they had proposed in their production plans. Management scrambled, and when finally caught up, stopped to do some analysis of what might have changed.

Nobody could think of why such a change would have happened, after so many years of happily using this procedure. Then someone remembered that several months before, a supplier delegation had come through the plant, talking, and discussing quality and productivity issues with their primary customer. It was likely that the supplier had noticed the swelling procedure in the tempering room, and recognizing that the price of shrimp was higher for the larger sizes of the shrimp, the supplier decided to start assisting the shrimp in their growth before freezing the blocks to ship overseas.

If you are going to sell a product that varies in price by the count, and not by the pound, make sure that you have the best count possible. It is a question of whether you can make a profit, or your customer will make a profit, you need to decide what is good for your business.

You will note that the final consumer did not benefit in this overall exchange.

A Productivity Story - Parking Meters and Work in Progress

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Years ago, I had the opportunity to visit a company building parking meters. The production floor seemed to be running smoothly, but I was surprised by the number of partly assembled parking meters sitting in Styrofoam shells around the walls of the production floor. There were probably several hundred units there, stacked five or six high, sitting side-by-side along the wall. I asked the company what was causing this WIP? The response was that they were missing one part, so they had partly assembled units while waiting for the part to arrive. I pointed out to the company that it might have been smarter not to even start to build the units until all the necessary parts to complete the units had arrived. You think you save time in the construction, but the company tied up a variety of parts that could have been used in other meters, and saleable stock could have been completed. Additionally, a lot of time and resources were used to stack units and place them against the wall. Last, but by far not least, there was the great danger of the stacks falling over and damaging the partly assembled parking meters.

As I moved through the production floor, I came across an assembly post where an operator was filing the upper section of the parking meter, so the top and bottom halves of the meter could fit together. He was adjusting each pair for a final fitting, as the castings were rather rough and needed to be adjusted. I pointed out to the company that they should stop this procedure immediately, and instead move to improve the quality of the supplier they were buying the castings from. The company asked why this was a problem, as the units all fit together when they left the company. I pointed out to him that the customer likely did not see the units as being a pair, but instead saw them as parking meter tops and parking meter bottoms and should be totally interchangeable. With this bit of insight, the company moved to remedy the situation, either by improving the quality at the supplier, or having all parts fit to standardize sizes in their plant. I did not have the opportunity to follow up on this project later, but my preference would be to work with the supplier to make sure that all tops and bottoms were interchangeable.

With any production schedule and situation, you must address not just what is happening within the production facility, but how your product is being used further downstream with your final customer and even beyond that with the consumer. At the other end of the spectrum, just what is the level of quality you are getting from your suppliers?

A Productivity Story - Simulation

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While visiting Avcorp Aerospace for an Innovation Insight, they told us a story about the optimization of the design for their metal cleaning tanks. When the company was designing the plant layout, they worked out some rough numbers about how many tanks they would need, what kind of chemicals, and how they would have to sequence the product through the different steps of the cleaning and washing procedures. The company then approached the local National Research Council Institute, which had a department dealing with simulation for process improvements. They worked with the scientists over several months and were able to optimize the proposed procedures for the systems. With improvements in the materials and the liquids, they were also able to bring these tanks out of a separate room (with separate ventilation) into the common room of the plant. I don't have the actual numbers, but I was told there was approximately a 25% reduction in the number tanks required (say 12 down to nine), a reduction in the size of the tanks, and an improvement in the flow process through the tanks from many hours down to just a couple of hours.

As with most designs, the engineers design over tolerance, then added extra on top of that. With proper planning, good scheduling, and an idea of how to run the products through, the simulation team was able to come up with a far better performance. The team was able to satisfy the management structure by showing them the results from the simulation to see what would happen, before the first tanks were even ordered.

A Productivity Story - Filling a Pallet

A Productivity Story - Filling a Pallet

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

I was working with a small food company on a consulting basis. Their product was shipped as frozen goods to several distribution warehouses scattered across North America. There were continual complaints from the distribution centers of missed product, voids in the center of the pallet and damaged goods. The main issue was that the company made 10 or 15 different products, and each of these products had a different carton size. When these cartons were mastered up with 12 to a case, we ended up with a variety of layer patterns on the pallet.

Operators can generate a pattern for the layout of these cases on a standard pallet. There is software out there to help you generate the optimum pattern to maximize the shipment. Most patterns can reverse from layer to layer, building a strong pallet of interlocking cardboard cases that with a bit of stretch wrap can survive just about anything that can be thrown at them by the forklift or cross-country shipping. Putting the different layers together to build an invoice for one of the freezer warehouses was a shipping nightmare, as no one was ordering full layers of product.

As a distribution warehouse would consume materials, it would order replacements using some variation of 10, 25, 50 or whatever they saw as a need to replace what was removed from the shelf. I thought about this problem and came back to a simple solution for everybody involved. The distribution warehouses did not really care precisely how much they received. They were just trying to refill the stock shelves. I reviewed the number of cases that existed per pallet layer. This was anywhere from 10 to 17, depending on the size of the cases involved. I took the order for the warehouse, say 25 cases of material, and divided it by the 17 there were on a layer, and realized I needed one and a half layers. But the truth is we do not want to ship one and a half layers. We want to ship either one layer or two layers. As the orders had been built and the operators put everything together from the odd numbers in the order, this often resulted in void in the center of the pallet. These were reported by the distribution warehouses as shorts on the invoices, and “thank you they tasted very good”. Always an issue when you are selling and shipping a food product, is that some of the food may be spoiled, and some may be evaporating into people's stomachs.

With a simple Excel spreadsheet, I divided the 25 by the 17 and then used the integer function to change the 1.5 to 1. I then added another one to give us 2, and instead of shipping 25 we shipped 34 cases. This was two full layers of the cases. We implemented this, and quickly got rid of the problem of bad invoices and voids in the center of the pallets. Operators on the shipping dock could look at a pallet, even one with three or four products on it, and quickly do the calculation of what was on the pallet and whether the correct numbers were on the invoice. One item would be a multiple of 17 while another item might be a multiple of 14 depending what number of cases were per layer. There were no more voids in the center of the pallet, and the people at the receiving end could quickly figure out that they got an accurate number, and everything was in place on the pallet. Additionally, the amount of broken cases and missing cases declined dramatically as the operators at the receiving warehouses realized there was not nearly so much opportunity to claim something was lost or crushed. The simple integer function in the Excel spreadsheet and saved the company many tens of thousands of dollars per year, plus a whole bunch of frustrating telephone calls and extra shipments.

A Productivity Story - Manually Turning a Corner

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While visiting a food processing plant, which was using inexpensive labor, I came across a novel situation of manpower replacing machinery. Due to size restrictions in the plant, it was necessary to turn a conveyor carrying boxes of food product 90° in a corner.

What this consisted of was one sloping conveyor moving into the corner, and then another conveyor at 90° to the first. The company had positioned on operator in that corner to transfer the boxes manually from one conveyor to the other. The operator was a young intelligent person and was smart enough to stack the boxes three high before turning and unstacking the boxes on the next conveyor. I can only imagine what they were thinking, as they perform this job for hours at a time.

After watching this procedure for five minutes or so, and realizing it was a full-time procedure when this conveyor and system was running, I approach the supervisor about making slight modifications. With the help of the operator, at the next break we cleared the two conveyors of boxes, pulled one section of the modular conveyor out, and pulled the rest of the conveyor sections into a rough curve. We tested the shape by rolling a series of boxes across the conveyor, with the weight of more boxes behind pushing the front boxes forward. Nothing fell off, and nothing jammed, so the cartons kept moving.

The supervisor, and the operator, happily agreed to the change, and the operator was moved to a different point on the line, where their services were more appropriate.

It should be remembered that a conveyor is not only a convenient way of moving things between points, but it is also a storage medium and a buffer. The key question here is whether the buffer is necessary in this position. The conveyor was creating another job as a necessity. It was far better to eliminate the conveyor, thereby eliminating that unnecessary job that came with it. The overall running of the line did not suffer from the reduction of this buffer.

A Productivity Story – Keep Asking Why

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While working in a major bottling plant, I was surprised by how a minor problem at the palletizing line could quickly turn into a shutdown of the can filling machine. As a rule, there are sections of automated accumulation conveyors between these two points. I could not understand why a packing issue of a minute or two at the palletizing post would result in a problem further upstream so quickly. I looked around for various reasons, and finally, one morning took the time to position and climb a long ladder to watch the conveyor, which was attached high in the rafters. It was a slightly ungainly observation post and brought some smiles and teasing from the operators. However, it was the only way to really see what was going on up there, as the conveyor wound through the rafters. What I found was that at some point in the plant history, the company had bought an automated conveyor designed to move the cases through yet act as an accumulating conveyor as things backed up. However, over the years various parts of the conveyor had started to break down, and so this accumulation conveyor was no longer doing the job it was designed for.

The correct design of an automated accumulation conveyor was such that cases coming into the conveyor should sweep through at high-speed to the end, and be palletized. Each subsequent case would attempt to do the same thing, and the sections of conveyor would remain empty through most of the day. If there was a stoppage at the palletizing post, the automated systems were supposed to kick in. The conveyor would start to accumulate cases, and this occurred for several minutes before the line was so backed up it shut-down the filling machine. As the conveyor had aged, and parts of it had broken and not been replaced, a whole new system of flow on the conveyor had emerged.

The first case would come up to the first integrated section of the conveyor, and it would stop there and wait. Shortly after, another case would come along the conveyor and push the first case forward to the next section stop. This process repeated for 3 to 5 min., until the entire automated conveyor was full, and cases were leaving the end of the automated conveyor into the palletization post. The accumulation conveyor system had changed to a simple conveyor, serving no useful purpose other than to slow down the start of the shift, and later the end of the shift. The issue then arose at the end of the shift on how to get the last of the cases off the conveyor, and into the palletizer.

This is a classic situation of the machinery creating extra work, and the work methods and procedures having to adapt to the machinery wearing out. What should have been a benefit to the packaging system became a hindrance. A simple sloping conveyor would have been a better solution than the expensive automatic conveyor system that was broken.

A Productivity Story - How to Skin Perch Bellies

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

While visiting the production floor, I noticed that the perch bellies being cut from the perch fillets were not being skinned. They were frequently flesh side down and missing the skinning machine, and so they had to be cut out manually and were just being tossed into the fish meal conveyor. There was a lot of flesh present in those perch bellies, and I asked whether we could put them through the skinning machine. The supervisors and the operators pointed out that this was a difficult and time-consuming manual operation on such small portions.

As an experiment, I took a pan with 1 or 2 gallons of fresh bellies in it, and loosely dumped it onto the feed belt of the Skinner. Surprisingly, 80 to 90% of the bellies were grabbed and skinned by the skinning machine in a normal fashion. Only 10 to 20% came out the far side with skin still attached. An operator would then toss these bellies, with the skin still on them, back into the front side of the machine, which was only a foot or two away.

The result was that we were able to produce a lot of skinned product, which could be used to make fish blocks. The value was far greater than the fish meal that most of this product had been destined for. The fascinating part for the supervisors and operators was that the machine did not really care about the orientation of the small belly portions. The machine just grabbed for whatever was part of the material, which always turned out to be the skin side. This would not happen with large fillets, where the skin side definitely had to be facing down, but these were small portions and could adjust themselves easily into the machine, and so they turned out to be self-orienting.

Never assume that you know what is going to happen inside a piece of machinery. And how long does a small test take?

A Productivity Story - Ergonomics of the Tringle Gun

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Years ago, while a supervisor in the extrusion department, I was exposed to my first case of carpal tunnel syndrome. These days it is called repetitive injury syndrome. At the time this was a new area of ergonomic problems in the plant.

Summer workers were hired for vacation coverage and were assigned to make labor-intensive tringles. These are the hoops that keep the tire on the wheel rim. This was reasonably heavy work, and so young broad-shouldered males were assigned to this post. Like most production posts at the time, there was piece rate work being paid to the operators. Some of these young follows became very productive at this post, and quickly started making up to three times as many of the tringles per shift as the older seasoned operators. This went on through the summer, until a supervisor happened to glance into the break room before shift start one day. He noticed a summer student flexing his hands and loosening up the fingers. He asked him what was happening, and the student said he had to loosen his wrists up before he went to his post, as he was getting a little burning sensation in the wrist.

The supervisor wisely sent the employee to see the nurse. The nurse had recently been reading about the carpal tunnel syndrome and took a quick tour out to the shop to look at the post in question. Upon seeing the post, and the complicated work being done with the tringle gun, she went to the shop manager and ordered the limiting of production per shift and per operator on the post. The shop manager had been happily watching the increasing production numbers and wanted to give some mild argument to this limitation. The nurse quietly explained the economics of an injury like this, and the cost to the medical system to look after an operator. The shop manager quickly realized that short-term productivity gains would in no way balance the human and economic costs to the operator.

This shop manager did not want to give up his productivity, nor risk long term harm to the operators, even at the reduced volumes. He formed a team with the Maintenance manager, to replace this manual tool, with an automatic machine. As I remember, it took about a month, and involved seven or eight prototype guns. By the end of the month they had a simple device with a manual trigger, that was capable of meeting or exceeding the quality of the work being done before. They even took the time to save all the prototypes and put them up on a sheet of plywood, as a plaque.

This is an impressive example of a company noticing an ergonomic problem, and immediately moving to limit the damage to the human operator, and then moving on to determine how to replace the human efficiency with a machine efficiency. We do not have to meet our production goals through the backs of our workers.A Productivity Story - Chain Manufacturer

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

Hi folks, I’m Walter Wardrop, an Operations Management Coach at the Growth Roundtable.

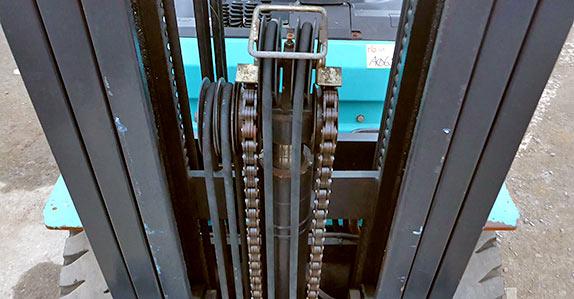

Several years ago, I went to a medium-sized metal stamping company that made large, specialized chains for a variety of industries. The product was basically like a bicycle chain, but on steroids, as each link was three to 15 inches long. These massive chains would work in the basements of large mills, both locally and around the world. The company had invited me out as they heard I could help companies look at their layouts and help them improve the layout, and possibly the productivity.

I walked into the company and looked around while being led to the office. I got to the office and asked the client about all the pallets I saw sitting out on the production floor. The pallets were your standard 40 x 48, with sides on them about two and a half feet tall. I asked if those pallets held about a ton of cut metal. The manager replied that they did. Then I asked how many pallets the company had. The manager replied that they had just over 400 pallets. I responded to the manager. “You are telling me you have 400 tons of cut metal floating through your plant?” Manager responded by saying they had three or four forklifts that were able to move the metal around quite easily. The company had 400 tons of cut metal floating through the plant! Then I asked the manager, “Was it last week or the week before that the supervisor asked for permission to weld up another six of these pallets?” The manager stopped short and said, “It was 10 and how did you know?” My response was that I did not know, and I was just taking an educated guess.

We now went for the tour, going through the plant looking at the different stages of cutting, welding, and stamping into making up this chain type product. Upon returning to the boardroom, I asked the manager if I had gotten all the steps right and laid out the sequence. I then asked the manager how long it took to make an order of chain. He requested that I keep it quiet, but they told the customer they could make it in three weeks, but frequently, they did it in two.

I had seen about five steps, and at the time we were touring had asked about the speeds of the different processes as we went by them. The manager said my steps were correct, and my speeds were accurate. My next point was to turn the speeds of the machines into seconds per unit or per step. I proceeded to outline the five steps, and the number of seconds involved. I said to the manager that if I put on some sneakers and welding gloves, I could make a piece of this chain in less than two minutes. The manager shook his head, and said no, but then stopped and thought some more about the times that I quoted, and realized that yes, they could make a piece of chain in less than two minutes.

The company called me back in a month and told me they had made an order of chain in less than an hour. In a subsequent visit to the company, I spoke with the manager and asked him how his profits were. His response was that the company now had four times the capacity within the existing facility, and had about 40% of the space available for sublet as they did not need nearly as much area as they used to consume. They had gone from having 400 of the pallets down to 125 pallets which are now color-coded, designating the difference between tempered or untempered metal components of chain.

The manager of the company asked me what he should do with the stacks of empty pallets sitting in the yard. I told him there were three things he could do with the empty pallets. First, you send them to local metal recycling facility and get some value from the metal. Second, if he is mean, he could sell them to his competition, across town or in another province. And third, with a smile on my face, I said if he is extremely mean, he could give them to his competition.

Another little story I remember him telling me. When he went to visit one of his subsidiary facilities, he asked them to implement lean manufacturing systems into place. The plant manager said it would not happen. His response was to look him gently in the eye and ask him which part of the terms boss and paycheck he did not understand. The subsidiary has since implemented the procedures, and that made everybody’s life much easier and more productive.

From a Canadian productivity point of view, this was an excellent success story. Prior to this point, the client was manufacturing in China chain of a size of less of less than 5 inches. Anything under 5 inches in length was done in China due to the inexpensive labor rates over there. Anything over 5 inches was done in North America, due to the high cost of shipping from China, offset by a labor. With the improvement in procedures in the flow through the plant, the company was able to take back the three to 5-inch chain to North America and leave China with the one- and 2-inch chain products. We can cost effectively manufacture in Canada, but we have got to stop stepping on own toes with our wasteful productivity habits.